Khasi Heritage: The Transgression

Nevertheless, the wren keeps poking and insisted that they should listen to what she knows. When there were no other alternatives, Syrmoh and Syrphin decided to lend their ears to the tiny creature. Still, the wren bargained with them and set a precondition for her vital information. Initially, she told them that the tiger came to lick the cutting marks on the trunk and that is how it get restored. Syrmoh and Syrphin were astonished to find that out but could not think of how to deal with the situation. Further, the wren offered her idea to the pair on the condition that they would allow her to feed on the extreme portion of the paddy field. Both of them thought that it was worthwhile to agree to the wishes of the wren, because it is hardly anything as compared to the magnitude of the cultivation field and the cause for demolishing the giant tree. Then the wren instructed them to lay down their axes and machetes with the razors exposed forward after every evening of a hard day's work. The tiny bird affirmed that in the dark of night, the razors would chop away the tongue of the tiger. The deal was done and the wren flew away. Mankind fell into the simultaneous temptations of both the mammon-serpent and the wren.

That evening, all the people were asked to place their cutting implements as instructed and Syrmoh and Syrphin were anxious and apprehensive of the outcome. Early the next morning, it was found that the trick worked with a few implements smeared with blood stain. From that day, the tiger never returned to the spot until the people succeeded in tearing down the giant tree. Simultaneous, at that precise moment, the golden vines on top of the Sohpetbneng peak also detached from the Mother-earth. Mankind rejoice in the false triumph of falling down the Diengiei tree, which represents nature and the entire environment on earth, which coincided with the end of the golden era, where humankind ignored and neglected the divine force.

The people were jubilant in the celebration of casting away the dense foliage from the giant tree, which was speculated that the canopy would engulfed the entire earth. Instead, nature lamented over the misdeeds of human beings and a lump of dark clouds impregnated with suspended vapours appeared in the sky ready for the torrent of rain shower. Nevertheless, merriment continued with the chanting of Phawar and folk dances till they reached their settlement and finally, everything came to a halt because of the deluge. A couple of the old men were apprehensive about the entire operation and repented. They stayed back at the hilltop and sought divine intervention. One of them is an inhabitant of the settlement at the foothills of Sohpetbneng and the other has already migrated to the plain land.

That was the beginning of the new era of suspicion and doubt, of trespass and intrusion, of sacrilege and desecration, of illicit and criminal indulgence, of wickedness and evil and so on and so forth. The ray of hope for mankind lies with the two wise old men. There is a misconception, even in contemporary situations, that light is being restored with the felling of a Diengiei tree is but a sign of the onslaught of modern civilisation. It is up to the beholder to provide a conclusion to the significance of the myth. The fact of the matter is that every creature endeavours to strive for their own survival and favours anything to suit their selfish interests. The mammon-serpent desires to retain his habitat and is never bothered about the well-being of the tiger and, moreover, he was contented with revenge over his partner in crime. The wren is anxious to survive with easy access to the paddy field of humans and ignored the vital requirements of other animals, in this case the forest for the tiger. The reality prevails that part of the forest cover should be sliced to create cultivation fields for humans and to provide staple food for the birds and the metaphor of the golden vines depicts that the navel of an infant needs to be detached from the womb of the mother, as between the umbilical cord of the earth to be delinked from the universe. The law of nature is mandatory that every creature and human being needs to be free from the clutches of natal conception, and must toil for sustenance and survival. The parable in this part of the story is the extravagant greed of the mammon-serpent and the mischievous trick of the wren who causes havoc in the world, because they refrain from toiling and achieve a reward out of their righteous duty, whereas the tiger, a sylvan deity to protect the environment was severely sacrificed at the betrayal of both the mammon-serpent and the wren. This is the manifestation of the perpetual relevance that persists in the world throughout the generations.

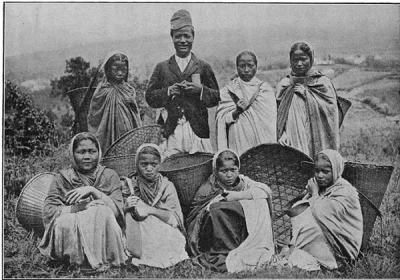

The two wise old men who stayed back after the flood are an indigenous Khasi and a migrant Dkhar. Both of them prayed to divine force and sought for penance on behalf of the entire humanity. They admitted to Ka Meihukum and Thawkur that mankind had strayed and ignored the sanctity of the sacred words of the divine laws. They may not be aware that Syrmoh and Syrphin fallen into the temptation of the mammon-serpent and obeyed the tricks of the wren, but they anticipated something was not right in society. The silent witness of the omniscient divine being showered blessings upon mankind and handed over to the two old men, separate sets of covenants containing the divine laws inscribed in legible scripts with instructions to be taught to the entire human race. When the divine task is completed, the two wise old men are ready to depart and as they climb down, they discover a massive flood of water with a mirage of their native land at a great distance. Both of them decided to swim across the river and devised a technique to protect their sets of covenants. The migrant or Dkhar man ties the leaf of covenant in his braid of hair on his head, but the indigenous Khasi man bites the leaf of covenant in his mouth and begins to swim. Both of them landed at separate destinations; the leaf of covenant of the Dkhar remains in tact, but the Khasi man swallowed the leaf of covenant while he fathomed the river current. When both of them reach the shore in their respective native lands; the Dkhar man is equipped with written scripts on the leaf of covenant, while the Khasi man could not produce any leaf of covenant and share his divine knowledge orally. This is the reason why Khasi folk literature is passed down through tales around the hearth with melodious chants and the rhythm of musical instruments, usually Duitara, Marynthing or Mieng. On the other hand, the Dkhar plainsman treasures the divine chronicles in the ancient palm leaves known as Buranji. Since then, the indigenous Khasi people and the migrant Dkhar people have cultivated their independent lifestyle and distinct cultural traditions.

U khla u jliah dien mong, na metbah jong u Diengïeï;

Miet sngi u ap hi dngong, la dapdoh na kat ba dei.

Da buit sianti ka phreit, ka wait u sdie la pynap shrip;

U khla te la khaweit, ba thylliej u phot khlem tip.

Kyntang ïawai rasong, ka pap bynriew te ha pyrthei;

Khyllem naduh dyngkhong, pyrthei mariang la i shyrkhei.

La dkut ka jingkieng ksiar, mar ïa twa te u diengïeï;

La wai ka kiew ka hiar, nalor bneng te sha pyrthei.

Bynriew te u sakma, shaïong ngaiñ u khyndai trep;

Jutang te ka la pra, la byrsieh ki hynñiewtrep.

Lyndet na hukum blei, sdang khie im ka kuli juk;

U thlen te ha pyrthei, ïa bynriew um ai jingsuk.

La luiñ tyrsim ki reng, sur ba syiang te ki lah rew.

Apot ki mrad ki mreng, ki sim ki doh ha jrong ryngkew;

Phyllung ki wah rymphum, skum ki ksing te lah lynsher;

Dohkha dohpnat ha um, ki khñiang ki ksiah ba par ba her.

Riewblei arngut jympa, la shlei um hap jngi wahbah;

Thiedsnam pur ki khana, ki dak thoh ha thiar la rah.