Khasi Heritage: Legend of Sier Lapalang

The triumph of good over evil is interpreted through the legend of Sier Lapalang, where the stag from the plain land comes to intrude into the hills because he was anxious to taste the flavour of the herbs and met with the consequence of losing his life and the lamentation of his deer-mother. The elegy narrated by the deer-mother emphasised the disobedience of the stag, in spite of the earnest appeal and warning by the mother, which led to the tragedy and anguish. This traditional perception is contrary to the independent interpretation from a different perspective, where the brave stag was an adventurer par excellence who dared to sacrifice his life to fulfill his ambition to achieve in life. The stag may have disobeyed his deer-mother, but he had a goal at least once in his life: he should taste that fragrance of herbs from the hills, which engulfed his desire and ambition to let the world know that he did it, even if he had to face the danger to surrender his life, but he was satisfied to die a victor.

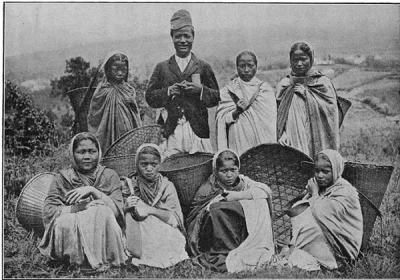

The body of the stag was taken to the village with jubilation and merriment to rejoice over the successful feat for the community and the land. On arrival in the village, an incantation was performed to appease the deities and offer obeisance with the sacrificial items from the flesh of the stag. The meat from the stag is distributed to all the villagers with certain privileges earmarked for the maiden shooter and hunting dog. Different territories have distinct traditions according to the encounter of a specific animal, that are harmful to the well-being of the community. There are areas that are vulnerable to particular wild animals, like stags and deer, tigers and boars, foxes and jackals, and many others depending upon their respective endemic region. Therefore, the highland areas are different from the slope and lowland areas, because the folk hunting tradition is not poaching for consumption and other profitable purposes, but strictly adhered to the safety and well-being of the community. The folk hunting tradition goes with incantation to seek the permission and endorsement of the divine forces before any attempt to identify and capture the genuine culprit. The tradition goes that if the tiger plunders the crops or catches the domestic cattle from the village, then the divine permission based on the incantation of the shaman is indicative of a specific tiger and not any other animals. Therefore, in folk hunting tradition, it is a violation to catch any animals other than those indicated through incantation, meaning that boars or foxes cannot be hunted in exchange for tigers, irrespective of the prospect or benefit. Moreover, after the folk hunting expedition, the killing and slaughtering of animal flesh goes along with the pardon before the divine on behalf of the hunted animal. The hunter will seek forgiveness from the divine before aiming an arrow and the priest will ask for the approval of the divine before performing the sacrificial rites and ceremonies. This is the justification of ecological balance, according to the Khasi folk tradition. It is the fulfillment of the purpose of human beings to prevail on earth, unlike the so-called modern civilised way of opportunistic attitude and self-interest.

The legend of the Sier Lapalang stag is assumed that it ascended from the plains of Bengal and the destination for the Jangew Jathang herbs was at the foothills of Shillong peak, while the catch was at the foothills of Diengiei peak. In this regard, the tradition of folk hunting of stags often prevails in the villages surrounding the Diengiei peak and for tigers and leopards are more prevalent in the southern slope region, particularly Nongtalang village. There are east and west altars known as Phlong Mihngi and Phlong Sepngi at Nongtalang, where the traditional tiger festival and ceremony called Rongkhli was regularly held till recent decades. After the folk hunting expedition, the clouded leopard was usually brought to the Nongtalang village at the sacred home of the priest for performing of rituals and ceremonies. In this case, the tradition is similar to the legend of Sier Lapalang, where the leopard would be carried in a makeshift hearse and carried around the village amidst the dancing and chanting of Phawar to celebrate the triumph of good over evil. Thereafter, the leopard would be slaughtered and the head be detached for sacrificial offering at the altar to be followed by the folk dance of the male members during the day, while the dance of female members took place at night. It is a tradition that the placement of the leopard at the altar should be done alternately whenever auspicious occasions of folk hunting expedition take place.

The conflict of interest between the authorities and the traditional institutions arose after rampant poaching by unscrupulous commercial hunters had threatened the survival of the species. The auspicious occasion of folk hunting was rare and with divine sanction, according to the ancient belief system and with reverential ecological consideration. However, the commercial exploitation by poachers is a hindrance to folk tradition that the State administration had to impose common regulations for the protection of endangered species of wild animals. Therefore, the vibrant tradition of folk hunting expeditions and other allied ceremonial practices was forced to be discontinued and affected even the cultural aspects of the tradition. The fundamental tradition of folk hunting expeditions, called ‘Ka Ksaw Ka Kpong’, portrayed hunting as a dire necessity to prevent the intrusion of wild animals into human society and the magnitude of casualties is disastrous to the plundering of crops, cattle and even human lives. The cultivation fields of the village folk are located more often on the periphery of the jungles, where medicinal and edible herbs, mushrooms, wild bees, tree bark and other forest products are the potential consumables of both humans and animals, including insects. The law of nature is facilitated in a manner to caters the necessity of all creatures, and there are times when humans chase away animals from the cultivation fields and the animals chase away humans from the jungles, and the outcome is the survival of the fittest and harmony prevailed in spite of the consequences.

There was an interesting episode of animal and human assertion for survival, sustenance and harmonious coexistence, vis-a-vis the artificial intervention of regulation by authorities. There was an instance where wild animals regularly plundered the crops and cattle of human society and the villagers utilised their indigenous knowledge to chase away the animals. The civil administration endeavoured to protect both the people and animals by creation of artificial barriers to demarcate their respective territory. The wild animals trampled on the artificial barriers and intruded into human territory until an alternative solution came through professional poachers, who indulged in illegal poaching in the guise of protecting human lives and the authorities are the silent witness to the entire episode with the complicated involvement of unscrupulous elements that devastated both human and animal welfare.

Hoi Kiw! Ka Ïew Luri lura

Pahuh te ba dang rhah, nang kyrdit u ba kyrduh;

hap shop ka jynjar trah, la sepei ki kam ba khluh.

Sianti ka shet kylla, ba la threw kumno ban khwan;

Ha ïew luri lura, laiphewmrad u khih u khan.

Ka skei ka sier tamti, ïa ka tungrymbai u ksew;

La pdok ka dang thylli, ba kiwei ki nang kynshew.

Dang die tungtoh u dom, laiphewmrad ki thom naphang;

Sma dien u ksew na lum, ksaw ka kpong te ba ka sdang.