KHASI MATRILINEAL CLAN LINEAGE: CLAN CONSECRATION

The Khasi custom would not accept any other ethnic community to be forcefully converted to the Khasi community through marriage or any social circumstances. This is in accordance with the law of natural justice where the ethnic origin is maintained and retained with the source of the racial origin. In case of intercommunity marriage, the children born out of a Khasi mother and father of different community are directly accepted as the legitimate offsprings of Khasi community because of the matrilineal system of clan lineage. However, the children born out of a Khasi father and a mother of another community are required to undergo through the consecration ceremony of a new Khasi clan ('tangjait 'tangkhong), while the mother retain her ethnic identity, even as she is being regarded as the original ancesstress, while her daughters became the first ancestral mothers (ïawbei khynraw) and her sons the first ancestral maternal uncles (suitnia khynraw) of the new Khasi clan (ka jait ka khong). The mother of such children is accorded respect of her ethnic origin and given due honour for her role as the ancestress, and on her demise a special cromlech will be erected to deposit the mortal remains of her bones with proper rituals.

If the past has so much knowledge and wisdom about life, the present is congested with excessive information about material possession. Therefore, society should ponder in the value system of the past and create the vision and journey for the present to guide the future generation. Likewise, the kinship organisation should invest in intellectual discourse about the essence of the folk knowledge on the social and cultural structure of the ethnic clan and the communal kinship relation. The kinship organisations (Seng Kur) must conducted like a responsible traditional institution instead of facilitating social welfare issues. The priority should be emphasised on the foundation of the clan and its function according to genuine custom and tradition, while supplementary activities may be considered on social welfare matters.

The rites de passage is the fundamental ceremony performed by people of every culture all over the world. The Khasis of Meghalaya has a distinct tradition in this aspect and the naming ceremony is one such ancient custom that still prevails in this contemporary world, and it is still being practiced and relevant today, despite the widespread domination of modernity and Christianity. It is more interesting that the practice is significant and observed with religious fervour even in a cosmopolitan city like Shillong. This kind of ceremony is compulsory among people abiding the indigenous faith.

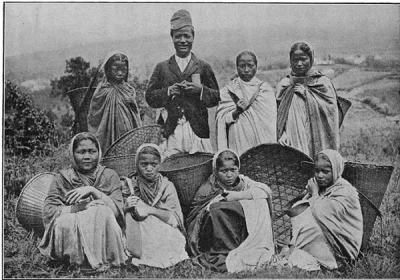

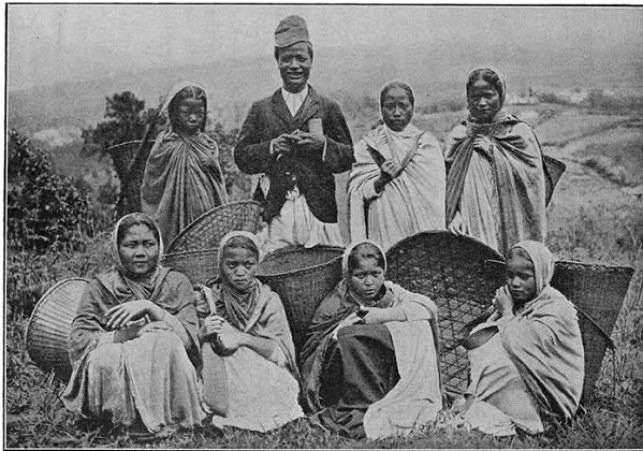

The elaborate ceremony comprises certain significant features that are related to the upbringing of the infant in every household. Moreover, there are different processes for male and female children. The implements used in the ceremony are indicative of cultural belief system. For the male child, the bow and arrows are used to confer a befitting name and for the female child, traditional bamboo basket (Khoh) and the carrying strap (Star) are used. Regarding the selection of appropriate names, usually the maternal or paternal relatives proposed a few names to be solemnised during the ceremony. To confirm that a particular name is suitable for the child and is considered divine approval through the final morsel of rice grain gripping the tip of the egg shell for divination and the lingering of the droplet of rice beer at the tip of the gourd. Another significant aspect to endorse the ordained name is the marking of lime paste on the child and all the maternal and paternal relatives. It is a usual custom to host a feast with the initiation of the pounded rice flour (pujer) to every relatives and well-wishers.

The traditional custom in Khasi society accorded immense reverence to the paternal mother (kmiekha) as the provider of a father, the progenitor (thawlang) who is responsible for the increase of the clan of his wife. In this regard, the children of a Khasi woman married to a man of another racial origin with a different culture is deprived of the traditional counselling and, in some cases, the affection of a paternal mother, which is considered the ultimate gift any child can receive. On the other hand, the children of a Khasi man married to a woman of any community is believed to be have enormous prosperity, because of the great fortune of proper guidance and warmth from the paternal mother.

In the Khasi customary belief, a family with many children is considered to be very fortunate, akin to possessing material wealth even without having any money and possessions. However, a person without children, even if he/she has an enormous amount of wealth and properties, is considered poor. Society and relatives are always worried about the family which does not have any children, and least bothered about material wealth, if they just have adequate food and shelter. It is perceived that tangible resources will be exhausted by usage, wear and tear, while the intangible resources of sustainable life will persist for generations, as long as nature and the surrounding environment generate ample reserve for every being to maintain their body and soul. This folk concept is translated into a congenial communal bondage in society.

This custom became a legacy in the community that has been cherished and prevailed through the ages. In the modern social structure, the custom has evolved into a process of charitable contribution by every member of the community to render assistance to any people that encounters adverse tragedy and misfortune. The voluntary subscription in the villages at the rural areas and localities in the urban areas are being supervised and monitored by the voluntary collectors and the voluntary council of elders in the villages or localities. This solidarity among the community is also extended to any migrant residents provided that the respective affected family participated and abide by the social convention of the locality. This collective responsibility is being enforced with a great sense of duty by the respective residents in their individual capacity, while the monitoring mechanism is in place under the authority of the headman and the executive council. This practice is neither the custom nor the religious procedure, but it is based on the founding principle of ethnic culture and became the original local tradition. The tradition of trust with the mechanism of expert management and the credential of the entire oral system has been sustained through the test of time. In addition, some of the large clans have also introduced such a system among the clan to contribute to the welfare of the deprived members of the clan in certain incidental consequences. This is the dynamics of traditional customs and practices.

This dynamic practice is the outcome of the ethnic concept of inclusion and resulted in the growth of liberal and tolerant society. In the past the Khasi practice is relevant as long as the tenets of folk customs are abided in true spirit. In the past, there were many clans in the Khasi community, which emerged from the marriages with other community, particularly for Khasi men with women of other communities. All the Khasi clan with the prefix 'Khar' are the result of such situation, where the new clan must be consecrated to ensure and affirm that the generation are considered of Khasi descent. As for the women who married the men of other communities, the custom is simple because Khasi matriliny interpreted that all the offsprings born out of a Khasi mother is considered Khasi, irrespective of the ethnic origin of the father. Unfortunately, this concept was destroyed by the intrusion of British colonial supremacy and the onslaught of Christianity, which imposed a bigoted and prejudiced model during the last two hundred years. The paradox is that the consecrated clans of yore have passionate allegiance and understanding of the Khasi milieu, ostensibly better than the original clans. This situation is being substantiated even in the modern context, where several people of such a family background have been instrumental in the growth and development of the Khasi cultural heritage.

Presently, there is a strange social development where the other deprived section of communities manipulated the system with forced conversion to avail the political and social benefits granted by the government machinery within the purview of the national law. To a great extent, the protection mechanism under the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution of India and the traditional institutions have been able to apprehended such discrepancies with proper analysis and scrutiny. Moreover, there is an awareness that alerted the original inhabitants to check and investigate these types of manipulation, especially when it was defended discretely by the certain section of the original Khasi community for selfish benefits.

Therefore, individual concern should not override the collective interest of the community, because the natural course of social change is gradually motivated towards the assimilation of the indigenous community with the dominant migratory communities due to social, political and economic factors. The theory of certain social scientists revealed that the Aryan culture would reach the foothills of the Himalayas within a certain span of time. However, the ethnic isolation and social resistance towards the alien communities in the neighbouring States of North Eastern India will enable to safeguard the assimilation process, lest the contemporary social structure of the Khasi people is vulnerable to the rapid changes. There is an established testimony at Tripura in this respect, where Bangla culture had almost overwhelmed the entire ethnic communities like the Deb Barma, the Reang, the Hrangkhawl and others. If the ethnic communities of the North East India, including the Khasi people, are to sustain and survive, there should have been a long-term measure to address the issue with strict vigilant and a broad-based strategy.